ONTOLOGIES - SOME PERSPECTIVES

Ontologies - why in the world would you ever need one?

ONTOLOGIES: SOME PERSPECTIVES

By W H Inmon and Jessica Talisman

One day the IT department of the corporation woke up and found that they had a big collection of applications. These applications ran many aspects of the business:

● Sales and marketing

● Account management

● Order processing

● Shipping

And a lot more.

THE APPLICATION JUNGLE

Each application had been designed separately and apart from any other application. Collectively, the applications formed what can be termed a “jungle”. Trying to pry reliable and accurate information from these applications was a real chore, a very inexact science. Some corporations were successful. Many other corporations were not.

BELIEVABILITY OF DATA

The problem with the application jungle wasn’t that data could not be found. Actually finding data was not difficult at all in the application jungle. What was difficult was believing the data had an accurate value once you found the data.

In the application jungle, the same element of data exists in multiple places. And the element of data had a different value everywhere it existed. Finding the data was one thing. Trusting the data was something else.

Believability of data was a big issue in the analytics done that were based on the application jungle.

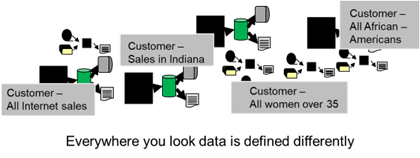

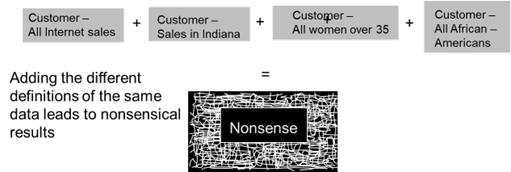

There were lots of reasons why believability of data was an issue. The primary reason was that everywhere the data existed it had a different definition. The data was named the same in many places, but the data was algorithmically inconsistent across the application jungle in the many places where it existed.

Because the same element of data had a different meaning everywhere it existed, trying to manipulate and use the corporate data meaningfully was an impossibility. There may have been a lot of data found in corporate systems, but using and believing the data was an entirely different issue.

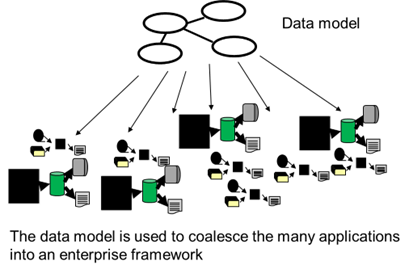

THE DATA MODEL

In order to provide a sense of coherency to the application jungle, a data model was created. The data model depicted how to unify the data in the application jungle. The data model provided a map as to how to unify the different applications found in the corporation jungle.

To use an analogy, a data model is to the data engineer or analyst what a compass and map are to a sailor. When on the ocean, the sailor is lost without a map and a compass. Any setting of the rudder is good when there is no compass or no destination.

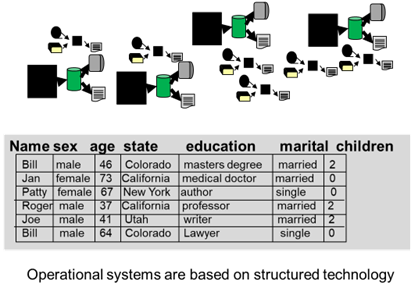

STRUCTURED DATA

The data that was found in the operational environment was – almost exclusively – structured data that has been collected into a database. Each row of data in the structured environment has a uniform structure. The only difference from one row to the next is the actual contents of the row.

Each row of structured data has keys and attributes which uniquely identify the row. Programs examine the structured data and select rows to operate on based on the value of data that has been found.

TEXT

While structured data makes up the vast majority of data used in corporate business, a different kind of data has entered the corporation. That data is called text. Text is natural language. Text appears as a result of writing or speech. It is how humans communicate.

Text appears in many places:

● Internet searches

● Email and messaging

● Conversations

● Spreadsheets

And many more places. Furthermore, text carries with it some very important information.

Text is very unstructured. While business transaction related data is highly structured, text is very unstructured. Because text is unstructured, it has a hard time fitting into a classical database format. Yet there is still great value in using text as a basis for making corporate decisions.

OBSTACLES

There are many reasons why text is so difficult to use as a basis for decision making. One of the main reasons is the double and triple meaning of the same word.

What does the word “fire” mean? Fire can be a conflagration. Fire can mean the pulling of the trigger of a gun. Fire can mean the involuntary termination of employment. And there are probably other meanings that can be attached to fire.

Without context, the true meaning of “fire” cannot be ascertained. Therefore, in order to understand the meaning of “fire” you must have the context under which fire is spoken as well as the word fire.

But there are plenty of other pitfalls when dealing with text. Another simple obstacle to understanding text is negation. “The doctor said I did not have cancer.” The implication of this sentence is not that I have cancer, but the opposite – I do not have cancer.

Another obstacle is language itself. There is English, Spanish, German, French, Quechua, and many other languages spoken and written around the world.

And these are but a few of the many obstacles awaiting the analyst who wishes to make sense of text.

ONTOLOGY

Like structured data, text needs a unifying concept – a map and a compass – in order to decipher and understand what is being stated, whether it is written or vocalized.

DATA MODEL AND THE ONTOLOGY

In many ways the ontology is to text what the data model is to structured data. While the ontology is certainly different than the data model, they both play a similar role in their respective domains.

WHAT THE HECK IS AN ONTOLOGY?

So what exactly is an ontology?

The word “ontology” is widely used in IT circles, but hardly anyone knows what an ontology really is. One can look up the definition of an ontology, which typically describes it as a metaphysical entity dealing with the nature of being and existence.

The truth be known, there is much confusion as to what an ontology is. Whereas a data model has a fairly well known content and structure, ontologies are much less well known and understood.

The definition of the ontology mentions that it is a metaphysical entity. So does that mean an ontology is created at a séance? Are ghosts needed to conjure up an ontology? Is a hypnotist needed?

This paper is going to give the views of what an ontology is. Two views will be represented by two knowledgeable people: Jessica Talisman and Bill Inmon.

DEMYSTIFYING THE ONTOLOGY: A KNOWLEDGE ORGANIZATION PERSPECTIVE

Jessica Talisman

Let’s dispel the mysticism. An ontology is not a metaphysical conjuring, nor does it require supernatural intervention. The confusion stems from philosophy’s appropriation of the term—philosophers study “ontology” as the branch of metaphysics concerned with the nature of being. But in information science and enterprise systems, an ontology is something far more concrete and practical.

At its core, an ontology is a formal, explicit specification of a shared conceptualization. Translation: an ontology is an agreement about what things exist in a particular domain, how they relate to each other, and what we call them. Think of it as the ultimate controlled vocabulary—not just a list of approved terms, but a complete knowledge structure that captures concepts, entities, attributes, properties and how these things are related.

Where Bill’s data model provides a blueprint for how to structure and store data in databases, an ontology provides something different: a semantic framework for what that data means and how it relates to the real-world concepts it represents. A data model says “Customer ID connects to Order ID through this foreign key relationship.” An ontology says “A Customer is a type of Legal Entity who participates in a Purchase Transaction that results in an Order, and these concepts carry specific semantic properties that hold true across any system that implements them.”

THE LIBRARY SCIENCE FOUNDATION

While ontologies are seemingly new ways to model and represent data, ontologies have been quietly running in the background of services and applications such as Wikipedia, The Getty, throughout government, Google search, Amazon products and so on. So why ontologies and why now? Ontologies draw from a rich tradition of knowledge organization systems—controlled vocabularies, thesauri, classification schemes, and authority files that librarians have been building since the Library of Congress Subject Headings emerged in 1898.

What’s different now? We’ve formalized these knowledge structures using semantic web standards that make them machine-readable and interoperable across systems. The ontology is expressed in formal languages like OWL (Web Ontology Language) and RDFS (RDF Schema), with controlled vocabularies managed using SKOS (Simple Knowledge Organization System). These open standards are the infrastructure that allows knowledge to move seamlessly across applications, organizations, and even industries.

WHAT MAKES AN ONTOLOGY DIFFERENT

An ontology differs from a simple controlled vocabulary or taxonomy in several key ways:

Formal Logic: Ontologies use logic-based reasoning. They can infer new knowledge from existing statements. If the ontology knows that “all Customers are Legal Entities” and “Legal Entities have Tax IDs,” it can infer that customers must have tax IDs, even if that’s never explicitly stated.

Rich Relationships: While taxonomies typically capture only hierarchical “broader/narrower” relationships, ontologies model the full spectrum of relationships: part-whole relationships, causation, temporal sequences, functional dependencies, and domain-specific associations.

Property Inheritance: Concepts inherit characteristics from their parent concepts in defined ways, creating reusable semantic patterns.

Constraints and Rules: Ontologies can specify what must be true, what cannot be true, and what is possible within a domain.

ONTOLOGIES IN ACTION

Consider Bill’s “fire” example. A properly designed ontology may will disambiguate the many meanings of the word “fire”, with definitions, by way of a hierarchy and finally, with context-rich relations between concepts.

Fire (polysemous concept)

├── Combustion Process (physical phenomenon)

│ ├── controlled fire → has purpose → heating, cooking, signaling

│ └── uncontrolled fire → has characteristic → destructive

├── Weapon Discharge (action)

│ ├── performed by → Agent with Weapon

│ └── has target → Entity or Location

└── Employment Termination (organizational action)

├── performed by → Manager or HR Representative

├── affects → Employee

└── has cause → Performance Issue or Organizational Restructuring

The ontology captures the underlying conceptual structures that let systems understand which meaning applies, in context. When processing the text “the manager had to fire the employee after the office fire,” the ontology provides the semantic scaffolding for distinguishing these uses.

THE ENTERPRISE ONTOLOGY CHALLENGE

Corporations face the same challenge with ontologies that they faced with data models: the temptation to build siloed, application-specific versions. Just as the application jungle created data chaos, ontology silos create semantic chaos—different departments defining “Customer” or “Product” in incompatible ways, even when using formal ontology languages.

The solution parallels Bill’s data model approach: create an enterprise ontology that provides the common semantic foundation. This doesn’t mean one massive ontology trying to capture everything. Rather, it means:

● A core upper ontology defining fundamental concepts (Entity, Event, Role, etc.)

● Domain ontologies for specific business areas (Sales, Supply Chain, HR)

● Application ontologies that specialize and extend the domain ontologies

● Clear governance ensuring semantic alignment across levels

ONTOLOGIES AND THE AI REVOLUTION

Here’s where ontologies become critical for modern enterprises: Large Language Models are a form of generative AI which makes them pattern-matching marvels. Generative AI lacks the structured knowledge representation that ontologies provide. Ontologies are a form of symbolic AI , providing a healthy counterbalance to pattern matching through semantic grounding. Without semantic grounding, LLMs will generate plausible text about your business, but they don’t understand your business the way your operational systems need to.

Ontologies give AI systems the semantic grounding they need to move from pattern matching to actual reasoning. They provide:

● Explicit business rules that AI must respect (not infer probabilistically)

● Concept definitions that remain stable across contexts

● Relationship constraints that prevent nonsensical conclusions

● Hierarchical knowledge that enables proper generalization and inference

Ontologies

BUILDING PRACTICAL ONTOLOGIES

The mysticism around ontologies often comes from overcomplicated academic examples. Practical enterprise ontologies should:

Start with existing controlled vocabularies: Your organization already has glossaries, data dictionaries, and term lists. These are ontology precursors—formalize them rather than starting from scratch.

Use standards-based approaches: Build on SKOS, Dublin Core, and industry-specific ontologies, like FIBO for financial services or Schema.org for e-commerce, rather than reinventing the wheel..

Design for interoperability: Express concepts using URIs (uniform resource identifiers) that can link to external ontologies, knowledge bases or be leveraged as linked data. Your “Customer” concept should connect to standard definitions, not exist in isolation.

Maintain governance rigorously: Like data models, ontologies decay without governance. Establish clear ownership, change management processes, and regular review cycles.

Make it machine-readable, human-understandable: The technical implementation may be expressed in RDF, JSON-LD and OWL, but documentation and data models should clearly explain what concepts mean and how they’re used.

THE COMPASS AND MAP FOR MEANING

Bill’s analogy of the data model as compass and map for structured data perfectly extends to ontologies for semantic knowledge. Where the data model helps you navigate the storage and structure of information, the ontology helps you navigate its meaning and relationships.

In an increasingly complex information landscape—where text, structured data, images, audio, and sensor data all contribute to enterprise knowledge—the ontology provides the semantic foundation that makes integration possible. It’s not metaphysical. It’s not mystical. It’s the essential infrastructure for organizations that want their knowledge to be findable, understandable, and usable across systems and over time.

The question isn’t whether your organization has an ontology—you do, even if it’s implicit and chaotic. The question is whether you’ll formalize it, govern it, and use it strategically to bring semantic coherence to your information ecosystem.

THE JOURNEY TO AN ONTOLOGY

Bill Inmon

I never wanted to end up knowing anything about an ontology. My entire journey has been a search for how to solve a problem. Ontologies found me. I didn’t go looking for them. They just appeared as a result of the quest we were on.

Let me explain.

One day a few years ago I sat down and posited the question – structured data makes up less than 5% of the data in a corporation. Text makes up 95% or more of what passes through the corporation. Yet corporations ignore text as if it didn’t exist. Corporations make 95% of the business decisions based on 5% of the data. Does this make sense?

The answer is – of course it doesn’t make sense.

So I started on the journey to discover what was required to come to grips with text. How could an organization start to include textual data in the decision making experience of the corporation?

When I started this journey I had no appreciation for the complexity of the task. Today I do appreciate just how difficult trying to get a handle on text really is.

The were MANY facets to this question. But the core problem – far and away the hardest challenge - was that text explicitly required that it be accompanied by context. Text without context is meaningless.

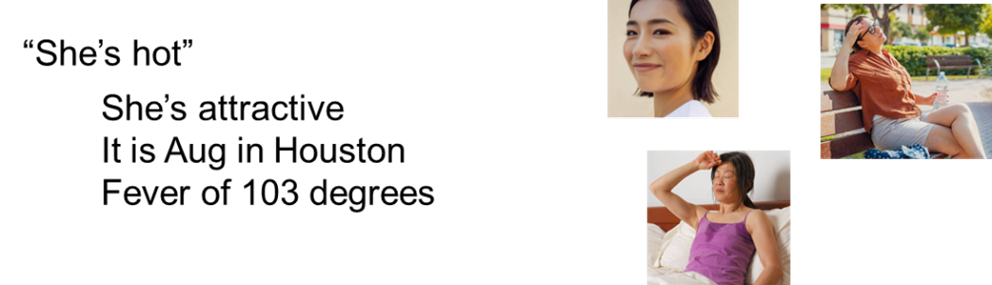

As a simple example of the value of context, two guys are standing on a street corner and one guy says to the other as a young lady walks by – “She’s hot”.

So what is meant by – she’s hot?

One interpretation is that the lady is attractive. The young man would like to have a date with her.

Another interpretation is that it is Houston Texas on a summers day and it is 98 degrees and 100% humidity. The lady is pouring sweat. She is physically hot.

Yet another interpretation is that the two gentlemen are doctors and the lady is a patient at the hospital. One doctor has taken the lady’s temperature and she has a fever of 102 degrees.

So when someone says – she’s hot – you have no idea what is meant until you understand context.

If you want to understand the meaning of text, it is non negotiable that you have context and well as text. Non negotiable.

The question then becomes – where do you discover context when you are trying to work with text? Having worked with text for over two decades, context is 90% of the problem and text is 10% of the challenge facing the analyst.

It is into this challenge that it was discovered that one of the best places to address the need for context coupled with text is in something called a taxonomy.

So what in the world is a taxonomy?

Simply stated a taxonomy is a list of words – a vocabulary – that all have a similar relationship to a common categorization. A taxonomy can be a vocabulary of anything – sports teams, states, foods, medicines, car types, and so forth.

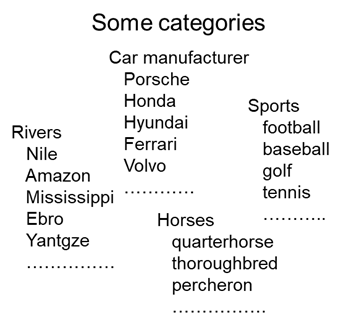

The following figure shows some categories and vocabularies.

Different vocabularies may or may not have an interrelationship. As an example of an interrelationship between categories, consider vocabularies for country, state and city. In this case there is a relationship between states and countries. Texas and Colorado are states in the USA. And Santa Fe is in New Mexico and El Paso is in Texas.

Note that the relationship is a very loose one. The country – Japan – has no states in the state vocabulary. In addition, there may exist London in the city vocabulary where there is no England or UK in the country vocabulary.

For these reasons, the interrelationship between vocabularies is a casual, loose relationship.

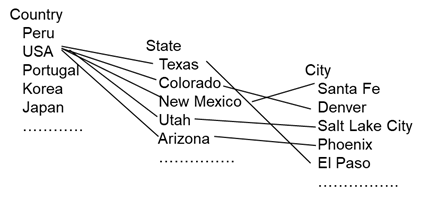

Now consider the vocabulary shown in the following figure.

Is this vocabulary a taxonomy?

The answer is that the vocabulary shown is only a common list of words. While many of the words in the vocabulary do relate to a car manufacturer, there are a lot of words that do not have a relationships to a car manufacturer – yupana, Bible, martini, hockey puck, and so forth.

Taxonomies can be gathered together to form an ontology. One vocabulary can be gathered with another vocabulary and together they construe an ontology.

There are an infinite number of ways that vocabularies can be combined. There are no constraints saying that one vocabulary cannot be combined with another vocabulary.

The most rational way to combine taxonomies into an ontology is to organize the vocabularies along the line of business organization.

[Note: there is no rule that says that ontologies should be organized this way. They can be organized any way that is desired. The reason why organizing taxonomies along the lines of business is that further processing using the ontology makes sense.]

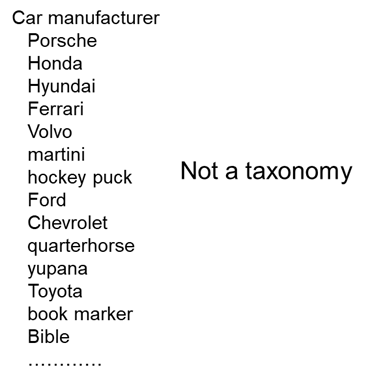

So what would an ontology organized along the lines of business look like?

An ontology organized along the lines of a manufacturer might look like

In this ontology there is vocabulary to describe business functions such as –

Accounting

Finance

Shipping

Sales

Manufacturing

And so forth.

Note that some of these taxonomies are generic to any business – accounting, finance. Other taxonomies are specific to the business at hand –

Manufacturing

Shipping

And so forth.

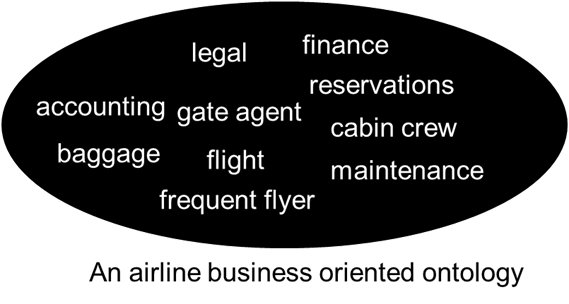

An ontology for an airline looks like -

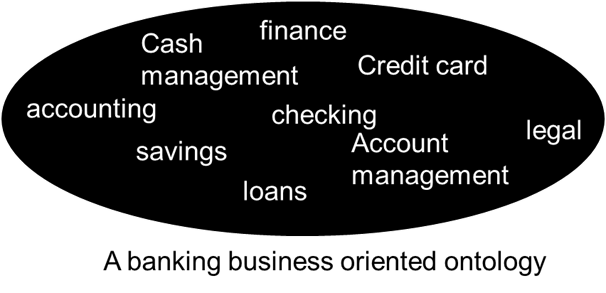

And an ontology for banking looks like -

So how can an ontology be used to unravel raw text?

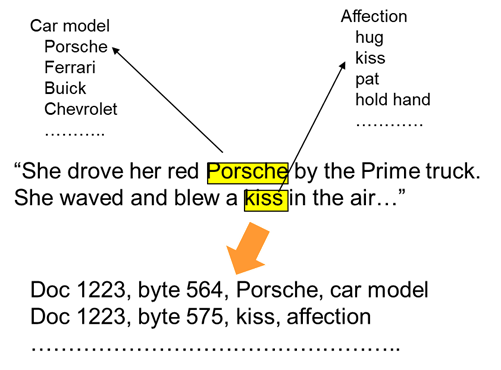

The following figure shows how an ontology might be used -

Suppose there are two simple taxonomies in the ontology – car model and affection. The raw text is read and when a word is encountered that is in a taxonomy, the word and its category are captured. In the case of this raw text two words are captured – Porsche and kiss. Porsche is found to be a car model and kiss is a form of affection. Car model and affection become the context for the words that have been encountered.

The words that are encountered are then placed in a data base with the context and the lineage of the word.

But something else has taken place here. The only words that are captured and placed in a data base are the words that appear in a taxonomy. But there are many words in the raw text that do not appear in a taxonomy. These words are simply ignored or discarded.

The fact that these extraneous words are not captured is a very good thing because this practice makes the processing of raw text efficient.

As a rule in raw text there will be many words that are not of interest to the analyst or ultimate user of the processing of the ontology. The volume of these words gets in the way of efficient processing. So ignoring words that are not of interest is a very good thing to do.

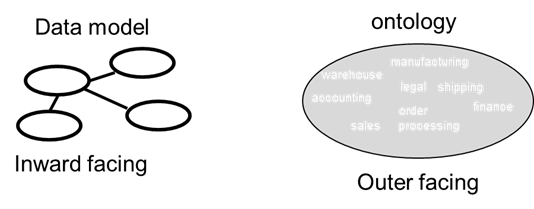

As a final observation, ontologies and data models play the same role to their respective audience.

Data models are used to organize and understand data across the structured environment. Ontologies are used to organize and understand raw text across the many sources of raw text that exist.

In that regard the data model and the ontology are the moral equivalent of each other.

But there is one very important difference between the two types of models. That difference is that the data model is internal facing and the ontology is external facing.

In order to understand this, the data model is created looking inward at the enterprise. The definitions and interpretations used by the data model come from the organization itself. The definitions and interpretations used by the ontology come from the world of common usage of language. And the common use of language is found far beyond the doors of the corporation.

This difference is significant because it profoundly shapes the way that the different models are created.

My own journey with ontologies was different than what most people experience, I believe. I started my journey wanting to solve a problem – how do you organize and understand raw text. Through trial and error we backed our way into an ontology.

One day we sat back and looked at what we had done and said – “this looks an awful lot like an ontology.” We built an ontology backwards.

Most people that I discuss this with go the other way. They start with an ontology and work their way into how to use it.

We did everything by trial and error. (And there were a lot of errors along the way.)

One observation about the approach we took. The end result was simple. One is struck at just how simple the final result was. I am sure academia can find a lot of ways to take simplicity and add features to it. All we ever wanted to do was to produce the results that we wanted. The simpler and the more direct the better.

Hopefully, upon reading this paper you can avoid some of the mistakes that we made.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

W.H. Inmon is widely recognized as the father of the data warehouse and has spent decades helping organizations structure and leverage their data assets for analytics and decision-making. Bill has sold over 1,500,000 books in his life

Jessica Talisman is a semantic infrastructure consultant and knowledge organization expert specializing in ontology development, controlled vocabularies, and enterprise semantic architectures that bridge library science principles with modern AI and knowledge management systems. Jessica created the Ontology Pipeline, a framework for building semantic knowledge infrastructures and ontologies.

Some of Bill’s latest books include –

DATA ARCHITECTURE – BUILDING THE FOUNDATION, with Dave Rapien, Technics Publications.

STONE TO SILICON – A HISTORY OF TECHNOLOGY AND COMPUTERS, with Dr Roger Whatley, Technics Publications.

Articles and presentations by Jessica can be found on Linkedin, Substack and Youtube.

What an insightful article by two awesome people, and I love the diversity of the examples!

Ontologies: For ONCE the term ‘analytics’ is used to mean something other than a ‘sexy’ catchphrase!

Some ‘tidbits’ of mine:

‘To use an analogy, a data model is to the data engineer or analyst what a compass and map are to a sailor.’

‘keys and attributes’: This is where my fascination with databases blends in well with my fascination with (I’ll call it) ‘Bill Inmon stuff’.

‘In many ways the ontology is to text what the data model is to structured data.’

‘“the manager had to fire the employee after the office fire,” …so many times I was that “employee” who caused the “office fire.” Please notice the difference between “...office fire,” and “office fire.”.’ Correct English?

‘In an increasingly complex information landscape—where text, structured data, images, audio, and sensor data all contribute to enterprise knowledge—the ontology provides the semantic foundation that makes integration possible. It’s not metaphysical. It’s not mystical. It’s the essential infrastructure for organizations that want their knowledge to be findable, understandable, and usable across systems and over time.’ ‘Ahh…that’s the ticket’, as Studs Terkel would say. . . .

And so what is the difference ‘tween ‘database’ and ‘data base’?